Over the last week, their courageous and passionate activism has hit the news headlines around the world while inspiring their peers in other institutions of higher learning in places as diverse as Waseda University in Tokyo, the universities of Sydney and Melbourne, the Sorbonne and Sciences Po in Paris, and Britain’s universities at Warwick and Bristol.

This snowballing campus activism has, in no small part, been helped by the ideological regressive nature of (usually technocratic) academics anointed as presidents. The latter typically answer to their Masters, that is, the organized money of the billionaire-donors, corporate interests and right-wing political forces of various imperialist shades, who hire and fire them, depending on the former’s use value and degree of subservience. There have also been stomach-turning video images of violent attacks against peaceful anti-genocide protestors by a 100-strong stick-wielding Israel supporters – whom Noam Chomsky would call Judeo-Nazis.

Although Chomsky’s reference was the new generation of Israeli whom the Zionist state has targeted for Nazi-esque “education” system whereby they all learn, from their early childhood, to fear, loath and look down on the native populations of Palestine, Judeo-Nazism has arrived on the American soil as is evidenced by the vicious attacks on peaceful encampments on UCLA campus while the campus police and authorities looked on.

As a Burmese revolutionary exile, whose country, formerly British colony (from 1824-1848), has a legacy of 100 years of campus activism, both non-violence and armed, against all types of unsavoury regimes, from white alien imperialists or home-grown Burmese dictatorships, I am writing this partially biographical, but primarily analytical essay in honour of American student activists and their supporters in the public at large.

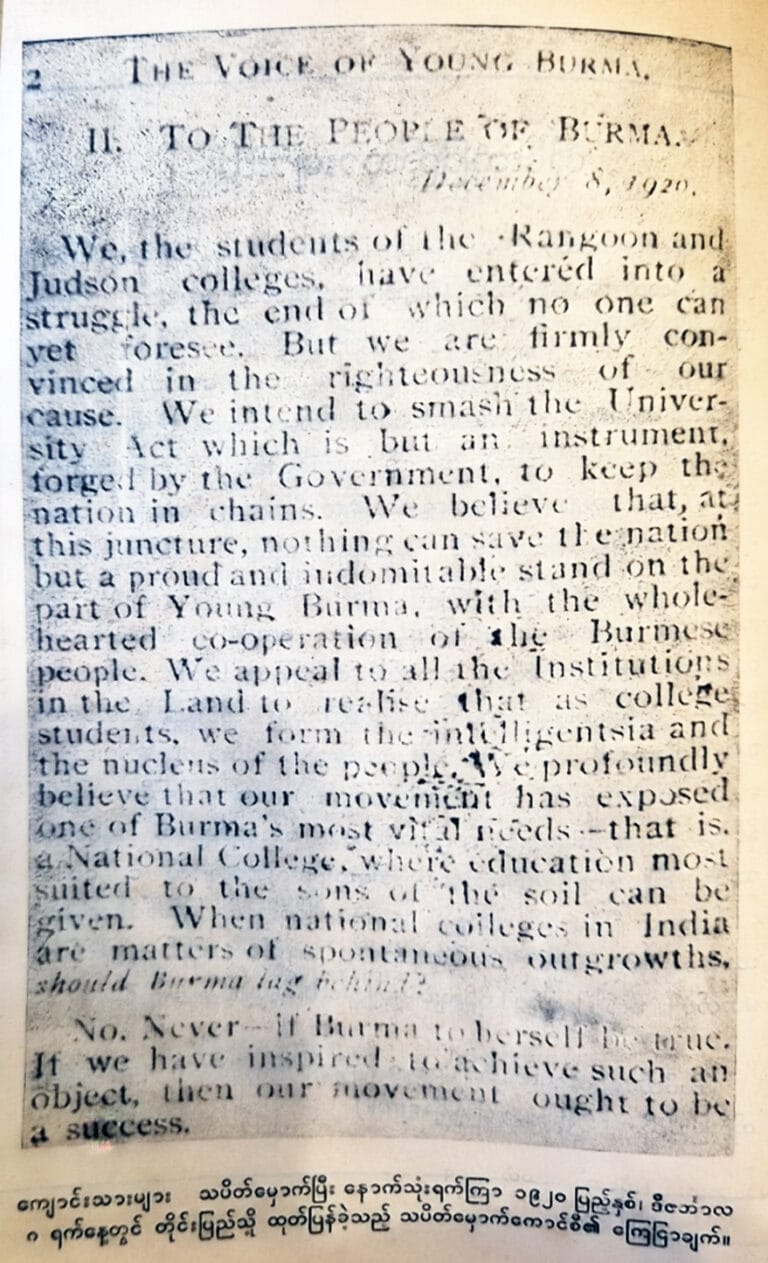

I revisited the 1st student strike against the British colonial rule, which was organized by a group of students, but in due course grew into a national education movement throughout Burma. The first line of the proclamation reads:

“To the People of Burma, We the students of Rangoon and Judson colleges have entered into a struggle, the end of which no one can yet foresee. But we are firmly convinced of the righteousness of our cause. We intend to smash the University Act which but an instrument, forged by the (British colonial) Government, to keep the nation in chains.”

– The Voice of Young Burma, December 8, 1920

The Voice of Young Burma.

The declaration to the nation of Burma, by the 1920 University Strike Group.

This first-ever strike against the British university education in colonial Burma came 3 years after Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution smashed the centuries’ old Tsarist tyranny, having driven chill down the spines of all European colonialists, particularly the British. It also predated, by nearly half-a-century, the first significant campus protest movement in the United States known as The Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964.

Well, the anti-imperialist Burmese student strikers of 1920 did not smash the University Act nor the British Empire. But the next generation of student activists the likes of whom, included my own great-uncle and his friend and classmate Aung San. did contribute to the downfall of the British Empire. They saw the World War II in Europe – and the Far East – as an opportunity to kill and bury the alien British colonial rule, which they experienced as the white supremacist apartheid that had been sucking their country dry for other a century.

After independence generations of my old country’s campus activists including my late parents’, generation have struggled against successive authoritarian regimes, largely military but occasionally civilian, which commit mass atrocities and systemic political repression. Presently, many thousands of Burmese university, college and even high school students have swapped their videogames and pens with AK-47s and “Kamikaze drones” to end 60-years of by the mass-murderous military junta.

But I did not learn to do campus organizing while I was a student in my city called Mandalay.

I learned everything about campus organizing in the relatively democratic context of the United States. I arrived at one of the 10 campuses of the world’s largest elite university system – the University of California (UC) – at the age of 24 in 1988.

Although I knew how to do neighbourhood organizing, thanks to my community-minded parents in our local community in Mandalay, Burma of General Ne Win’s dictatorship years in the 1960’s and 1970’s, I had absolutely no clue as to what it was like to engage in campus activism in a relatively democratic context such as US campuses.

The inspirational 1960’s revolts on campuses across the Western World (and former USSR) bypassed my country, which was closed off in Ne Win’s military coup in 1962, a year before I was born.

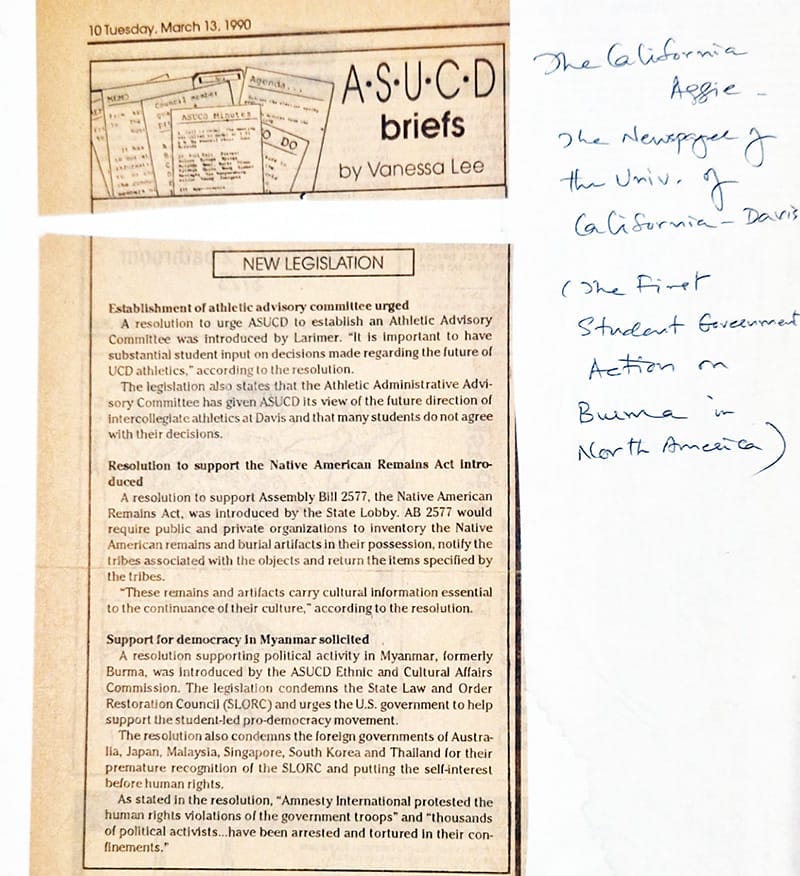

The University of California at Davis student government eventually passed the resolution, first of its kind US campus activism history, in support of Burmese student-led resistance against the military junta. The Burmese Association (of students and faculty) were involved in the lobbying efforts. I testified before the Student Government, March 1990.

At Davis campus of the UC, 80 miles north of Berkeley – and subsequently at the University of Wisconsin at Madison – I was impressed and inspired by how my peers learned to practise their citizens’ rights on campus, which felt like a microcosm of the American society at large. It was from these American peers that I learned campus outreach, crafting press releases, lobbying student governments, strategic communications (i.e., the use of all forms of mass media), public speaking, leafleting, chalking on public spaces, tabling and gate-crashing opportune public events and meetings, blocking traffic and other acts of civil disobedience and so on.

I learned from different generations of campus activists, as well as community organizers, who had used their intellect, moral energy and organizing talents and experiences in various social justice movements including the Civil Rights Movement, anti-Vietnam War movement and the anti-apartheid movement of divestment campaigns.

Years later as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, with its radical campus tradition, I was building and coordinating the Free Burma Coalition as one of the then pioneering human rights movements linked up through Netscape and dial-up modems across over 100 university campuses and community, feminist, human rights, labour and environmental groups in 28 countries. Thanks to my Free Burma activism, I had the honour and pleasure of serving as an activist trainer to hundreds of students at various activist conference.

After finishing my doctoral studies at Wisconsin in 1998, I was given an office space free of charge by Ralp Nader, one of the greatest American citizens alive, to further my activism at his Center for the Study of Responsive Law, an activist incubator, in Washington, DC.

The American students I have known and had the privilege of working with in my 17 years in the United States were the best, idealistic, down-to-earth, eager to learn or share, principled and compassionate. They were the complete antithesis of the military-industrial-media-university complex, run by mass-murderous serial criminals, Democrat or Republican, that fully embrace their own delusional sense of being “exceptional”, that is, SUPERIOR, to the rest of the human world.

So, a celebratory essay in honour of American student organizers is the very least I can do, as my show of gratitude and appreciation – and a small act of solidarity.

My very first engagement with campus activism was a rather uncomplicated act of donating my brand-new sleeping bag to a group of American students who camped out outside the main administration called Mrak Hall and staged a days-long hunger strike, demanding that the administration honour the pledge of constructing a multicultural centre on an increasingly diverse campus, with large non-white student enrolment. Like many other elite campuses, Davis had by an established a tradition of civil disobedience dating back the anti-war movement of the 1960’s. UCD student protestors would block trains transporting anything related to Vietnam war, as the rail tracks are located not too far from the flat campus surrounded by agricultural research fields.

The Christian Science Monitor, 31 October 1995.

Newspaper clipping from the author’s campus organizer days of 1990’s during which he was coordinating the Free Burma Coalition, linked up via the then emerging Information Technology (Netscape and listservs) across 28 countries.

My mind rushes back to the oral history of our own Burmese campus activist tradition against the British rule. I learned about it from my own scholarship just as much as from my elders some of whom were direct participants in these mass revolt against the White Man’s imperialist rule of 124 years and the integral apartheid in colonial Burma.

Historically, Britain’s colonial education (including universities) in the colonies was to serve the multi-faceted interests of the British colonizer. Specifically, the Empire’s administrative machine in the 19th and the early 20th centuries was to be manned by the British-trained local elites, that is, young and ambitious but subjugated Indians, Africans, and Burmese (among others), who would be equipped with the relevant technocratic skills (for instance, land survey, petroleum engineering, agricultural sciences and (colonial) law but, equally important, who would be “Indian by blood and colour, but English by likes, beliefs, morality, and intellect.” (Worth reading the background of Thomas Macaulay, “(Britain’s) unofficial historian laureate” who came up with this rather arrogant but deeply ignorant architect of this Imperial Education,1834).

Colonies were maintained as an administrative pyramid at the apex of which sat a tiny number of young Oxbridge-trained white men whose sat at the desk, assisted by the local boys with colonial education, while protected “(by) one million bayonets”, as George Orwell put in his first ever novel “Burmese Days”.

The book is a brilliant take-down of the British Empire which the author knew first-hand as a Burmese-born, but Indian-raised English police inspector. It is every bit as good as his better-known works such as 1984 and Animal Farm. But its painfully accurate portrayal of the Empire as “a system of theft”, with the veneer of “civilization”, having no feature that is morally redeemable, did not endear itself to literary critics and publishing houses of Britain, hence its 1st edition was brought out by the American publisher.

It is this colonial cream of local crop who finally figured out that their nation’s bondage could only be ended with direct confrontation, armed and non-violence. This awakening of the colonized Burmese mind did not come about as the result of the official British curriculum. Many of the leading organizers of the 1920’s – and more significantly, 1930’s – came to be exposed to revolutionary and other radical ideas, analyses, and tales of militancy, from all continents, including – and most certainly – Karl Marx’s writings.

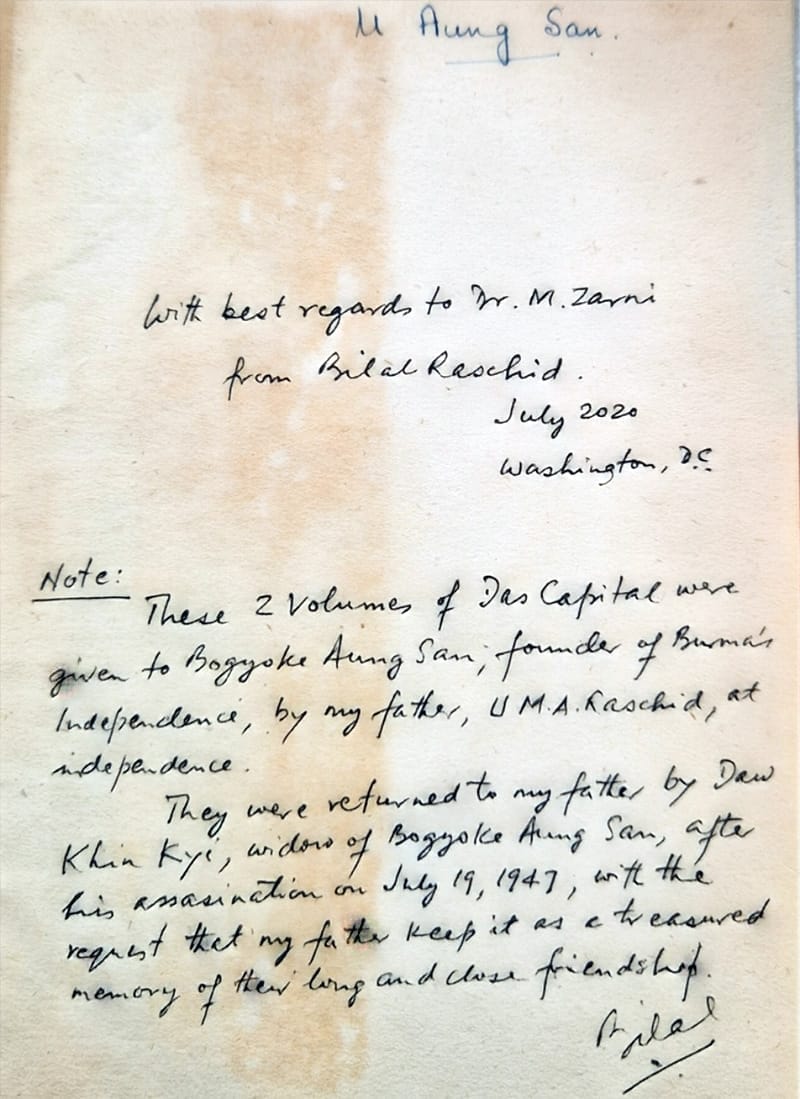

The cover of The Capital by Karl Marx, from the two-volume classic, that belonged to the slain Burmese Revolutionary leader and former Rangoon University student leader Aung San, the father of Aung San Suu Kyi and a friend and class- and dormitory mate of the author’s great-uncle. (Photo by Zarni).

Aung San, the unrivalled independence hero, was a Marxist-inspired radical who emerged out of the 1936 Inter-Class Solidarity Revolt against the British Rule. On the eve of the official transfer of sovereignty by Britain he publicly and repeatedly addressed the need to re-take the control of Burma’s key industries and natural resources from the British commercial interests. He was assassinated in less than 6 months before the end of the British rule. Multiple sources, Burmese and English, including my friend Rob Lemkin’s film “Who really killed Aung San?” (BBC Two, 1997) indicated clearly the British involvement in the murder in his cabinet meeting in Rangoon on 19 July 1947.

When the Great Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered worldwide economic crisis – and with it, diminishing economic prospects, Burmese students were already self-educating about the twin-evil of (White) Racial Capitalism and British Colonialism and building anti-colonial alliances with the multi-racial labouring classes in the British-owned oil fields of the Dry Zone. It was this convergence of their precarious post-university future and the critical understanding of the fundamentally terroristic and parasitical British rule which revolutionised the young local elite men and women of the colonial university and colleges.

These anti-imperialist Burmese a century ago rightly saw their colonial university as an integral component of the larger Capitalist-Colonial machine, with their morally repugnant “White Only” clubs, that is, apartheid, throughout the empire.

A similarly critical perspective on education – that the prevailing political and economic system of the United States, which replaced Pax Britannia after the World War II, turns young American elites into “machine parts”, having been churned out at “knowledge factories” – had emerged and informed campus activism of the 1960’s.

Here the late Mario Savio, an Italian American graduate student in philosophy at UC-Berkeley who became the iconic, if unofficial leader of the Free Speech Movement, delivered a scathing sit-in address wherein he famously indicted the universities as factories and presidents as (factory) Managers on 2 December 1964, before announcing that the last speaker was Joan Baez:

“– if this (UC-Berkeley) is a firm, and if the Board of Regents are the Board of Directors, and if President Kerr in fact is the manager, then I tell you something — the faculty are a bunch of employees and we’re the raw material! But we’re a bunch of raw materials that don’t mean to be — have any process upon us. Don’t mean to be made into any product! Don’t mean — Don’t mean to end up being bought by some clients of the University, be they the government, be they industry, be they organized labour, be they anyone! We’re human beings! … There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious — makes you so sick at heart — that you can’t take part. You can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.”

Demonstrating no such critical perspective, Robert Reich, a former hippie who protested against the anti-Vietnam war in the 1960’s who recently retired as Professor of Public Policy at the University of California at Berkeley, described the mushrooming campus protests around Palestine as a single-issue cause (of moral outrage against Israel’s mass atrocities against Gazans and the complicity of the United States in them put it in his short essay “What’s really motivating the protests?” (3 May 2024).

Here Reich, former Secretary of Labour in the Clinton White House with his incurably liberal capitalist perspective, offered a woefully inadequate analysis when he reduced campus protest movements across USA as simply a youthful expression of a single-issue moral outrage.

To get a better grasp of the campus protests beyond Palestine I turn to two perspectives: first, my old friend from Chicago, Jack Weinberg, whose solo arrest by the UC-Berkeley campus police, triggered what came to be known as the Free Speech Movement birthed in the beautiful flagship campus of the UC, and second, that of my own 24-year daughter, Dewi Zarni, who began her undergraduate studies at Barnard College/Columbia University and, in her junior year, transferred to UC-Berkeley where she completed her BA Honours in American Studies with a concentration in Race, Migration, and the Carceral State.

When I was teaching as a start-up tenure-track assistant professor at a regional teacher education university in Chicago a quarter century ago, I became good friends with Jack Weinberg, one of the pivotal figures in the Free Speech Movement. My then wife Annie Leonard, a renowned lifelong American environmentalist, and Jack were working together on the environmental health campaigns as activist colleagues, along with the likes of (medical) Doctor Peter Oris, a former President of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) at Yale.

A newly minted father, I was in my early 30’s and Jack was in his late 50’s. Despite our age differences, we bonded as radicals. I loved – and still do at 60 – learning from the veterans of the previous radical movements.

Those were the years in which Dustin Hoffman’s debut film The Graduate (of Mrs Robinson infamy) – which in fact was filmed on Berkeley campus – must have been set. In those decades university regulations restricted any type of activism including tabling, leafletting, outreach or fundraising on campus, by anyone other than the two existing political parties – Republican and Democratic. The subsequent anti-Vietnam campus protests were met with a form of organized violence – California National Guard – whose deployment was ordered by the then Hollywood 3rd rate cowboy-cum-Governor Ronald Reagan.

I am reminded that the British colonial authorities in Burma resorted to brutal and bloody crackdowns, expulsion from classes and university and other threats in dealing with non-violence anti-colonial protests in Burma in the 1920’s and 1930’s, as elsewhere throughout the Empire (for instance, India and Kenya). The social media videoclips and headline news of the campus crackdowns and early morning raids in USA have a long ideological and methodological connection to this age-old colonialist repression worldwide used by the European colonizers.

Jack told me that he was involved in the Civil Rights Movement led by the African-American activists who were already using in “sit-ins” as a method of public confrontation with the American apartheid institutions including schools, bus companies, and small restaurants.

As the young Jack in his 20’s was manning the table alone, distributing civil rights leaflets near the iconic Sather Gate on campus, the police arrived and demanded that Jack produce his identity card. When he refused, they arrested him and put him in a police van parked on Bancroft Street which runs perpendicular to Sproul Plaza. But several thousand Berkeley students surrounded the police van with Jack inside and prevented the police from taking their fresh arrest away for more than 30 hours!

With a chuckle, my famed activist friend recalled that he had to urinate in a Coco Cola bottle while having been kept captive in the police van while surrounded by the sea of his supporters.

Alas, what a relief it must have felt for a student activist with a radical anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist analysis to be able to piss into a Coke bottle that truly symbolized corporate America in full view of the cheering throngs!

In 1965, a year into the Free Speech Movement, Jack attempted to correct that misperception that the Movement was simply an extension of the Civil Rights movement. It is as relevant today as it is instructive to quote Jack’s own words at length:

“The University of California is a microcosm in which all of the problems of our society are reflected. Not only did the pressure to crack down on free speech at Cal come from the outside power structure, but most of the failings of the university are either on-campus manifestations of broader American social problems or are imposed upon the university by outside pressures. Departments at the university are appropriated funds roughly in proportion to the degree that the state’s industry feels these departments are important. Research and study grants to both students and faculty are given on the same preferential basis. One of the greatest social ills of this nation is the absolute refusal by almost all of its members to examine seriously the presuppositions of the establishment. This illness becomes a crisis when the university, supposedly a center for analysis and criticism, refuses to examine these presuppositions. Throughout the society, the individual has lost more and more control over his environment. When he votes, he must choose between two candidates who agree on almost all basic questions. On his job, he has become more and more a cog in a machine, a part of a master plan in whose formulation he is not consulted, and over which he can exert no influence for change. He finds it increasingly more difficult to find meaning in his job or in his life. He grows more cynical. The bureaucratization of the campus is just a reflection of the bureaucratization of American life.

As the main energies of our society are channelled into an effort to win the cold war, as all of our institutions become adjuncts of the military-industrial complex, as the managers of industry and the possessors of corporate wealth gain a greater and greater stranglehold on the lives of all Americans, one cannot expect the university to stay pure.

In our society, students are neither children nor adults. …

“It is their marginal social status which has allowed students to become active in the civil-rights movement and which has allowed them to create the Free Speech Movement. The students, in their idealism, are confronted with a world which is a complete mess, a world which in their eyes preceding generations have botched up. They start as liberals, talking about society, criticizing it, going to lectures, donating money. But every year more and more students find they cannot stop there. They affirm themselves; they decide that even if they do not know how to save the world, even if they have no magic formula, they must let their voice be heard. They become activists, and a new generation, a generation of radicals, emerges.”

FSM: The Free Speech Movement and Civil Rights by Jack Weinberg, Jan. 1965 (fsm-a.org)

Those were the written words of the veteran radical activist of Civil Rights and Free Speech movement written and published in January 1965, 3 years before the famous 1968 uprisings across the West.

You can copy, cut and paste them, and republish them with some tweaks, as a deeper analysis of the encampment movement against Israel physically destroying an entire captive population of 2.3 million Gaza.

To belabour the obvious, the United States Government led by self-proclaimed Christian Zionist Joe Biden is the chief patron of this genocide. Not unlike the authoritarian discourses of “law and order” – shared across variously repressive and conservative regimes, including colonial administrations, Leftist totalitarian regimes, military dictatorships and right-wing (US republican) governments such as Ronald Reagan, Joe Biden, rather despicably calls for “law and order” while distorting campus protests as “chaos” and “anti-Semitic”.

Since Jack penned these words in 1965, there have been new generations of radicals – with idealisms and analyses, beyond shallow liberal capitalist thought (or non-thought). With age, our bodies may decay, and our physical endurance may decline. But make no mistake our minds and radical ideas/idealism remain as sharp as when we were younger.

The author with Selma James (93), an American-born writer, feminist, anti-racist, and anti-sexist activist founder of Global Women’s Strikes, and a former student and widow of C.L.R. James. James’ ground-breaking work The Black Jacobins is an absolute must-read for anyone who wishes to understand racial capitalism and its foundational pillars of Slave Trade and Slavery. At the British-Burmese Trade Union Solidarity Event, Friends’ House, London, 20 April 2024 (in the background is Jeremy Corbyn with a Burmese-British activist Nichol Nyunt Han).

C.L.R. James. James’ ground-breaking work The Black Jacobins.

Enter Noam Chomsky, Richard Falk, Selma James, Ralph Nader and thousands of lesser mortals around the world who are cheering on as the new generation of radicals assume their rightful place in the forefront of social and racial justice movements. My own historian teacher the late Robert L. Koehl at the University of Wisconsin at Madison fought against the Nazis in Europe as a military intelligence surveyor in the United States Armed Forces in the 1940’s. In the 1960’s, as a scholar, he turned progressive anti-imperialist, when he concluded that his former employer was a mass-murderous corporate war-monger as evidenced in the senseless carpet-bombing and spraying of Agent Orange in Vietnam.

The often-told reactionary joke, “when you are young, but you are not idealistic. You don’t have a heart. When you are old and you are still idealistic, you don’t have a brain” remains just that: a reactionary joke.

Idealism does not age with one’s biological age.

As an issue, Palestine has come to embody what is systemically wrong with the corporate-run World Order of which presidents, be they the political states such as USA, or not so-high education institutions such as Columbia, UCLA or Wisconsin, are glorified Managers.

Angela Davis characterises it as “a moral litmus test of our time”. It may be so. But the issues surrounding Palestine are beyond Palestine.

The newer generation of young people, that of my own daughter and her peers – that is, Greta Thunberg’s generation – have been inflicted by the mental, economic and physical pains, anguish and anxieties by the very same System and the same ideological forces – Racial Capitalism, White Supremacy, and Patriarchy.

Reactionaries and Fascists of all stripes and colours, whose voices get typically amplified by the powerful corporate and mass media such as CNN, BBC and the New York Times characteristically attack what they consider “Hard Left” or “Climate Warriors” or “anti-Semites” (including Jews with Conscience). They will continue to do so.

But the young generations who stand up against a complex of mass-murderous oligarchies in USA, Canada, and formerly colonial criminal states of the old Europe (for instance, UK, France, and Germany) see their activism beyond Palestine.

In conclusion, I give my own activist daughter the last word.

Dewi Zarni (from left to right: at the protest against the World Bank in Washington DC, 1999); at a student environmental rally in San Francisco, 2012; and at the environmentalist civil disobedience, the Capitol Hill, Washington DC, 2018).

Three years before protests against Israel’s genocide in Gaza – and the resultant “encampments” across Western university campuses, Dewi Zarni writes in her “The End of the World (as we know it) (18 December 6, 2020),” (republished by Johan Galtung’s TRANSCEND Media Services):

“Halfway through my final year of college, it has become increasingly difficult to avoid thinking about the future. The prospect of having a career, a family, even growing old one day seems entirely fictional, something attainable for someone at some point in history, but not for me. Instead, I find it easier to picture familiar apocalyptic scenes composed of orange skies, burning forests, flooding, and human displacement.

My mom says that I’m being a pessimist, and she’s probably right. Maybe every generation feels this way at some point, that the scale of the obstacles we face is unprecedented and insurmountable, that we are the ones who get to witness the end. However, anxiety about the future is a defining characteristic of Gen Z. Our generation has the highest rates of loneliness, depression, and suicide, in addition to emerging phenomena such as climate anxiety and eco-grief.

In many ways, depression is a natural response to the circumstances. My childhood was fundamentally shaped by protests, school projects on global warming, and dinnertime conversations about rising sea levels. Our generation is the first to grow up at a time when the existence of climate change is no longer the subject of debate. We are also the last with any chance of mitigating its effects.

The anxiety that so often overwhelms me comes not from understanding the threat of the climate crisis, but from watching those in power repeatedly fail to take action. Growing up involved reconciling the knowledge that our future was in peril and the reality that this fact alone was not enough to create change. Many in our generation quickly learned that in the eyes of the government our lives hold less value than the stock market.

We are constantly reminded of this fact, as guns remain unregulated after countless school shootings, restaurants reopen amid a deadly pandemic that disproportionately affects Black and brown Americans, and the climate crisis — the devastating effects of which we are already seeing — is deemed too expensive to address. As is often the case, disenfranchised groups bear the least responsibility for these crises, yet experience the worst of their effects.

Weeks ago, when CNN finally called the election, I held no false hope that a new president would save us. The harm of another Trump administration would be irreversible and devastating, and his removal from power is cause for celebration, but while Biden’s promise of a return to normal will likely be celebrated over mimosas at many brunches, it is also a promise to ignore the real, life-threatening issues which existed long before Trump took office. As a young person of color, the daughter of an asylee, and a soon-to-be college grad, a return to normal means the continued failure to meaningfully address climate change, the militarization of our borders, student debt, and police violence.”

See the TRANSCEND MEDIA SERVICE » The End of the World (as we know it)

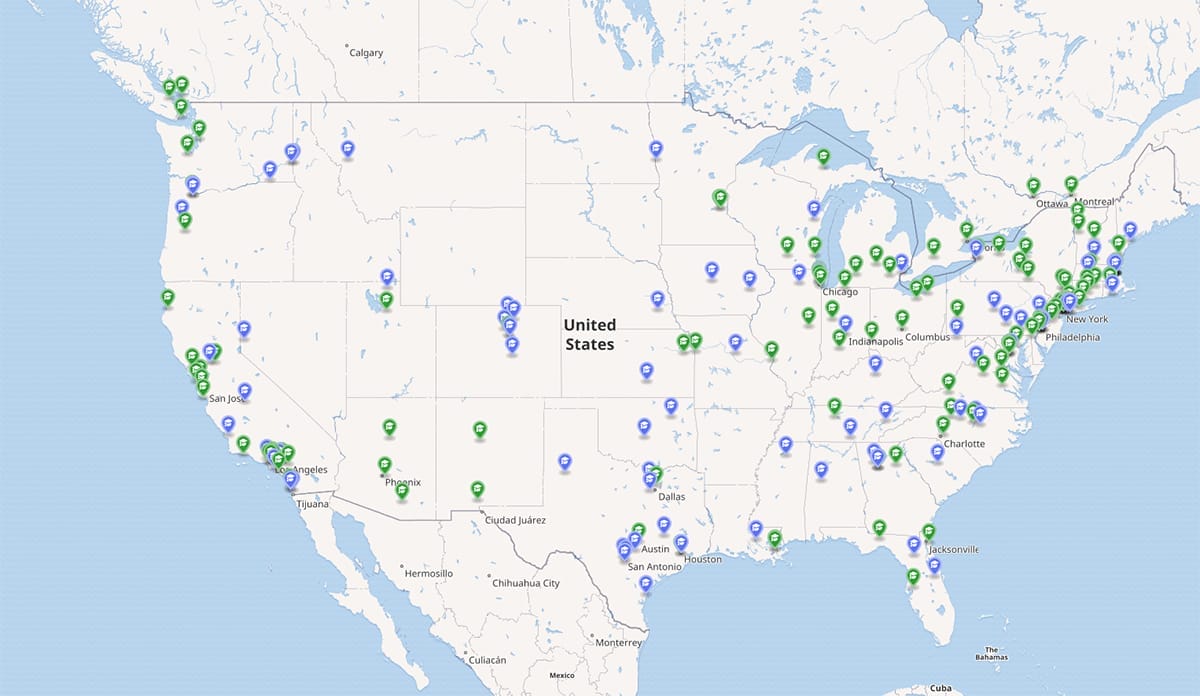

Universities in the United States with Israel–Hamas war protests in April 2024. Colleges that had encampments are marked in green, and non-encampment protests are marked in blue. Wikipedia Commons

I can’t help but wondering how many Dewis out there among the thousands of young campus protestors who see these ecological, global and national linkages which the Military-Industry-Media-University Complex has attempted to conceal from the public consciousness.

My daughter’s generation see beyond Palestine, just as the late Martin Luther King Jr. saw Beyond Vietnam 60 years ago.

They are wise beyond their age, unlike the Managers of the glorified “Knowledge Factories”, called Public and Private Ivy Leagues that in the final instance serve the agenda of the United States, the World’s Biggest Rogue State, in the process of its Neo-Fascist implosion.

Maung Zarni

Banner: Scenes of the reinstated Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Columbia University on its fourth day, 21 April 2024. Wikipedia Commons